Trying out this new "Note from the Field" format - lighter stories in between more in-depth posts

[This was motivated by this cartoon in this LinkedIn post by Rohan Chakravarty (@green_humour on Instagram), which was shared with me by colleague and podcast supporter Alessandro Badalotti]

I have always made a point of replying to emails from aspiring conservation researchers. I remember, with gratitude, the generosity of others who replied to my timidly earnest emails seeking guidance and connections when I was just starting out.

But I've definitely gotten distracted and forgotten to respond to a few such emails, especially while working a fast-paced job with IUCN in Myanmar. Actually, it was during that time that I encountered the only one of those emails that I consciously decided to ignore - "I... will not be spending time on this." My energy budget was stretched thin, as was my patience; had this young researcher emailed me at a different time, I likely would have been more gracious. I actually feel like I missed an opportunity to gently educate them. Ah well.

So, what was it about their email that turned me off? The main thing: they knew, from a mutual colleague, that I worked in Myanmar, and they'd "always wanted to study the Moken."

There was no explanation for *why* they wanted to study the Moken (commonly known as the "sea gypsies" of Thailand and Myanmar), or what, in particular, they were curious about. It reminded me of student emails that gushed, "I've always wanted to study dolphins!" It felt very... objectifying, in a way.

Moken are among the groups of sea nomads in Southeast Asia, which also include the Sama-Bajau and Orang Laut. They certainly are remarkable in many ways, with their deep connection to the ocean, along with the skills and traditions they've developed through that connection. It makes sense that many of us marvel at their way of life, so different from the lives that we know. It's akin to the widespread fascination around the Japanese ama and the Korean haenyeo divers (subjects of many media features). And it often relates to the widespread tendency to romanticize indigenous ways of living.

So, I don't begrudge this young researcher their interest in this group of people. But I simply didn't have the energy to patiently explain why I needed them to dig a little deeper into why this *interest* justified engaging with these people as *study subjects.* And I certainly didn't have the energy to tactfully explain why this tinge of entitlement was problematic, given the serious challenges that this highly marginalized group faces as their way of living is increasingly obstructed by dwindling resources, restrictive *conservation* regulations that erode their rights, and limited access to services that are more and more necessary as they are being forced to adapt away from their nomadic lifestyle.

The point is: I can be grumpy. The other point: Romanticizing indigenous people is all-too-common in conservation, and this can obscure the real humanity - including the rights and struggles - of these people. I, too, find the Moken fascinating, on a personal level. I also find their situation and context fascinating, in the way that researchers can find troubling, challenging, complicated topics "fascinating," since one of my main professional interests is how inclusion and power dynamics are incorporated into conservation processes. However: if I cannot think of a way that my research - my involvement - will meaningful contribute to their representation or well-being, I would never presume to insert myself into their ecosystem, so to speak.

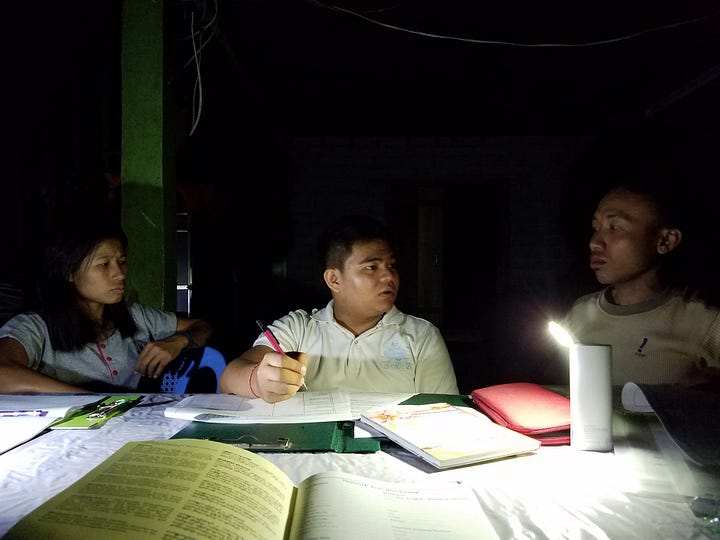

Now: I actually have, *extremely briefly,* done some research on the inclusion of the Moken community in conservation. I stumbled into it during my postdoc in 2017, which was looking at different forms of stewardship. In Myanmar, Fauna & Flora International (FFI) had collaborated with the Department of Fisheries and local communities to work toward Myanmar's first Locally Managed Marine Areas in Myeik Archipelago. I reached out to FFI to learn more about the LMMA and shared my interest in understanding how conservation processes impact (for better or worse) local stewardship. Turns out, the FFI Myanmar marine team was interested in the same thing, and invited me and my team (who would go on to found Myanmar Coastal Conservation Lab) to visit two of the LMMA communities to see what they thought about the LMMA process. One of FFI's main concerns? They had felt that they hadn't done as thorough a job as they would've like toward inclusion of Moken communities in the various consultations and decision-making processes, and were concerned about it.

We only had a handful of days, so this was by no means as thorough a study as I would've liked; fortunately, the communities were small, and we still gathered useful insights from LMMA committee members and other community members, including the local Moken community. What was obvious was that the Moken were literally living "on the margin" of the village - their neighborhood was at the far end. And it became clear that this was an apt analogy for their inclusion in the LMMA process.

Now, it's not that FFI hadn't tried to include the Moken. But this case was a great example of: "invitation does not equal inclusion." You can invite people all you want to different consultations or "co-creation" workshops or trainings, but if they don't feel that these opportunities are (a) accessible or (b) worthwhile, they very well might not show up. And if they do show up, and it turns out that the event was, indeed, not accessible or worthwhile, then your process still isn't inclusive. You can show that you had underrepresented or vulnerable groups in attendance, but in the end, that doesn't mean all that much.

What makes something accessible and worthwhile? That's... for another post. For now, let's say:

Accessible = the person can attend, understand, and actively participate in the proceedings. This includes issues of scheduling, transportation, language, cultural practices, and social dynamics.

Worthwhile = the person's participation can influence the outcome of the proceedings in a way that represents their interests and needs.

In the Myeik LMMA case, there was a substantial language and social barrier precluding the meaningful participation of the Moken in the LMMA process. They did not feel as if the consultations were an accessible platform, and did not feel comfortable joining. There was a sort of hesitation to join the process.

There were plenty of adorable moments with Moken kids flocking to us and guiding us around the village, and a local teacher working to teach these kids in the Moken language. But the moment that resonates the most with me was when an older Moken woman was shooing me and most of my team away from her patio (she was gentle about it). We'd found a group of Moken women that included someone who offered to translate for an interview. However, they only wanted to talk to Yin Yin out of the whole team. Yin Yin just has a special way with community members, especially women, and somehow these women sensed that. So, the rest of us stepped about 20 feet away to just chat and wait. But the women were "too shy" (as explained to me) even for that, so we had to turn the corner and get ourselves out of sight.

Yin Yin showed up, 2 hours later, breathless and full of important insights shared by these women. They had a lot to say, but needed to feel comfortable with who they shared it with.

[Oh my, I was hoping this would be a short post!]

Overall, stakeholders had a positive view of the LMMA process. But many of the negative components related to the lack of proper inclusion of Moken stakeholders (even non-Moken stakeholders mentioned this as a problem). This also led to a strong perception that benefits from LMMA-related projects and constraints on resource harvesting under LMMA rules were inequitably distributed, to the detriment of the Moken. The Moken interviewees shared that they did not feel comfortable joining the larger community consultations - they felt left out and confused by the proceedings. And because of this, they felt left out of the whole LMMA process.

One of the main recommendations from our brief little evaluation was that separate consultations or even small Focus Group Discussions, with trusted translators, would need to be held for the Moken. Their inclusion would need to be proactively supported and pursued. Remember: just inviting someone does NOT equal including them in a meaningful way. And, to their credit, the head of FFI's marine team at the time did take this feedback to heart. I'm really not in the loop as to what happened next in the LMMA process, so I don't know how this feedback was addressed.

As the cartoon referenced above says: There needs to be Moken representation, not token inclusion. The Moken are remarkable humans with fascinating way of life, but we cannot forget that they are *actual humans* who are impacted by conservation problems and decisions in very real way. And they have real skills and expertise that should be brought to the conversation about conserving ocean resources.

I hope this was a relatively light and fun piece to read. Next week is a hefty one - a dive into global inequality and its implications for conservation. Whew!

Let me know what you think, please. Do you have any other examples of well-meaning "invitations to participate" not panning out as expected? Is this type of narrative interesting at all, or should I stick to a more "professional" tone in my analyses? Was I too mean in not responding to that young researcher? I think I was...

Thank you, and take care!

Share this post