Welcome to Conservation Realist! I am Dr. Tara Sayuri Whitty, and I am very glad to bring you this episode, episode 18 - it is a special compilation from most of the interviews conducted over this first season.

And this compilation is of my guests’ responses to these three rapid fire questions. But, because of how my mind works, I had trouble actually choosing only three questions, so there's there's kind of three types of questions, and two of them have multiple options. Here they are:

(1) What is one thing that would improve how conservation functions or what is one thing that would make your day-to-day work in conservation easier?

(2) What is an unsung idea that you'd like to see get more recognition in the field, or who is an unsung hero you'd like to see get more recognition in the field?

(3) What is one of your top pieces of advice for aspiring or younger conservationists?

Now, anyone of the guests probably could have given a whole talk on each of these questions, but it was a really nice way to wrap up each conversation, just having a quick summary of their thoughts on these issues. They seem quite simple on the surface, but I think they do have a lot of power to offer insights regarding how we can make conservation a better field in many ways.

I am fully in the throes of pre-winter holiday madness, and I'm sure many of you are too, although I suspect that by the time you listen to it maybe we'll be already into the new year. But I kind of want to revisit something I touched on in the previous episode, which is: why, oh, why did I plan to make a compilation episode which would require me to go back and edit every single conversation that I've had for this podcast?!?!

It is a lot of work, but I understand why I wanted to do this. I think it's nice to get kind of a cross-section of the people who were featured in this first season. It seemed like a nice way to kind of wrap up the season and revisit the voices that we've heard from.

And I so very sincerely appreciate the time, energy and wisdom shared with me by each and every one of these guests during this first season. I do have another episode planned - I'm resolved to get it out by the end of the year, really just for my own personal timeline – but for now, this has been a big undertaking and I've been so very pleased and moved by how many people agreed to be interviewed and who expressed their support of this project.

I want to emphasize how much of an honor it is for me to learn from people like the folks who I interviewed in this season. There are so many people doing fantastic, thoughtful, creative work… [if you hear that rustling in the background, the resident cat has found some wrapping paper…] [meow] But yes, it's such an honor to learn from people like them.

And I know that when I talk about conservation as a field, I might strike some people as being very critical, perhaps pessimistic, maybe even “unpleasant” (and by the way, I find that to be quite a gendered critique), but I feel like those of you who are listening kind of get it. You know that this is coming from a place of being realistic, of being a “conservation realist” and knowing that

the pursuit of better conservation and that means conservation that's effective in an ethical and equitable way that goes hand-in-hand with social justice. It's not going to be improved by candy coating anything really. And so while I... Oh my goodness…[loud thud] The cat, again, has knocked over a stack of books.

What was I saying? Oh my goodness.

Okay. I know I can be critical of many things that many people in the broader field of conservation do. But I also am so excited and heartened by the wonderful, mindful work that many people are doing as well. And I find that unfortunately, a lot of that latter kind of work isn't necessarily given the attention it deserves in the way that I think it should be highlighted.

So again, I'm just very thankful that all these people who chatted with me who have so many other more important things to do, were willing to share their voices here.

I think this might have been one of my more discombobulated introductions, so maybe we should just move on.

Let's listen to a brief clip from the song Green Touch by Soe Moe Thwin, Zyan Htet, and Min Min from Myanmar, and let's dive into some of these responses.

[MUSIC]

All right, so question one: What is one thing that would improve how conservation functions? Or, what is one thing that would make your day-to-day work in conservation easier?

And here is Dr. JoMarie Acebes (Jom) from Balyena.org:

Jom: Can I say money?

T: Yes, money is important!

Jom: I don't know. There's so many things. Definitely people knowing the law. People being mindful of, basically, the laws that govern the species or the environment, and at the same time being mindful of the people who live on a particular species or habitat, and at the same time of your own limitations of what you can do given your position whether you're a government official or NGO worker or a scientist.

And yeah, I think definitely if we had, if everyone had the proper resources, not just manpower, definitely, it would make life so much easier for everybody. This is not just speaking for conservationists, but also for the government agencies who are mandated to enforce laws, for example. Because I don’t blame them for a lot of other things that are happening beyond their control, because literally they are just undermanned. There’s not enough to do the work that they’re supposed to do, and that affects everything, basically.

And now, Brooke Tully, Conservation Marketing Expert and Trainer:

Brooke: I would answer this coming back to one of our previous conversations, having those conservation marketing or behavior change communication roles be full time dedicated roles would be huge. I think again, for the effectiveness of those projects, and I mean, I would just love to be able to train, mentor and support folks who are thinking about this day in and day out as their full time job.

Next is Yin Yin Tay with Myanmar Coastal Conservation Lab (MCCL):

Yin Yin: This one I would say if we have like sustainable activities, like marine mammal research, and then we know ahead of time okay this year we have these activities and then we can design how to work and that can make it easier, easier for us. If not, we have to like, like change, change the activities and change all things, as I experienced before, and that is difficult to follow the new rules, new things to adapt.

If we have concrete activities and long-term activities for the future, that would be easier to move forward.

T: So like projects that have kind of long-term and reliable funding, for example, is that what you mean?

Yin Yin: Yeah. And in this case, I would separate like two, this one is more like budgeting and then like concrete activities.

Another one is working with a team. What makes it easier and effective is good giving of constructive feedback to each others and communicate with respect and openness in the team that make how to work like more effective and easier in the team as well.

Here's Thanda Ko Gyi from the Myanmar Ocean Project:

Thanda: …Money. [laughs]

T: Yes!

Thanda: And, and, and I don't know, a country that's back on track.

T: Oh, was that it? [both laugh]

Thanda: That would, that would immediately make everything a lot easier.

T: Well, I hope that happens sooner rather than later.

And this is Dr. Ruth Brennan, transdisciplinary researcher, policy advisor and integration expert based in Ireland:

Ruth: I think relating to something that I said earlier, that one thing that I would prioritise would be recognising more that we can conceptualise human nature relationships in more than one particular way, in multiple ways, and that it's not just instrumental, say, natural capital, cultural capital concepts, that is the way to conceptualize that. So yeah, acknowledging the multitude of ways that we can conceptualize how our relationships, society environment relationships are.

Chris John's National Geographic website cover boy and working now with RTI International:

Chris: Oh, I mean, that's easy. Money.

T: I feel like most people say that. Money.

Chris: Yep. That's it.

Here is Dr. Lucy Keith-Diagne and Diana Seck with African Aquatic Conservation Fund:

Lucy: That's easy for me. If the wildlife enforcement would actually enforce the laws. Because they’re not, so the wildlife is not truly protected here.

Diana: For me, that would be to get fishermen involved to stop the bycatch.

Dr. Rishi Sugla with the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington:

Rishi: I think education in so many ways can be liberation, and the way that we educate young researchers to do this type of work needs to so drastically change as a starting point, right? Like, how do we become engaged scholars? How do we not tie our hands to a publish-or-perish system when we're doing this type of work?

I think rethinking how we teach young early career researchers, it would be such a huge step towards creating this community that we talked about. And that is the generational work that needs to happen. It needs to be like rethinking what the cutting edge of learning how to do this type of work is, what it means to be a solidarity-grounded scientist – this would deeply help because we need community to do this work, you know, and it's hard to find that community.

Here's Jean Utzurrum, a consultant for the Marine Wildlife Watch of the Philippines and a member of several scientific advisory bodies:

Jean: I know you said these were rapid fire. I tried answering them last night and I couldn't. I couldn't!

I think, man, like I think just one way for conservation to work better, especially in developing countries, is for grants to cover full salaries for the applicant. Because, like I haven't applied for a grant in a really long time, but I've heard this from a lot of other people. You know, grants often don't cover salaries and this can be difficult for someone who's, for instance, like an independent researcher or working not in academia, because if you're working in academia, right, you have a monthly salary. But if you're independent, or you're with a nonprofit that's struggling to keep their head above water, not including salaries in the grants forces people to possibly take on two or three other jobs.

And so like, you're, they're overworked, essentially. And they might not be at their 100 best when they're working on conservation.

Sorry, that was not two sentences!

T: No, but that was a good answer! I fully agree that that is so important.

And Mark De La Paz, long term Irrawaddy dolphin conservation researcher in the Philippines, and now a PhD student at Hiroshima University in Japan:

For me, I realized conservation is very transdisciplinary or multidisciplinary. It's not just a biologist's work. It's a lot of people involved. And what I realized is education really plays an important role. So I think it's really important that we get passionate teachers involved in our cause. We communicate with teachers and students because, like I said, you never know, like, how much impact you just did by just giving a lecture. In the future, they're going to be protesting for you. So education is very important, I think.

And question two, what is an unsung idea that you'd like to see get more recognition in the field? Or, who is an unsung hero who you'd like to see get more recognition in the field?

Here's Jom's answer.

Jom: Fishers. Fishers know a lot more than they talk about, or talk about with researchers or scientists or even government officials. And I think they have very valuable things to say.

And from Brooke:

Brooke: I would love to see more recognition from the conservation field in particular to what science communicators are doing. And somehow these are two different fields. I'm not totally sure why.

But there's so many emerging leaders in SciCom that are, in my opinion, just doing awesome things in engaging people on the species that they study and their data and their science.

And I'm going to call out three in particular:

Sarah McAnulty, she does Squid Facts. Awesome. If you don't spend any time thinking about squids, you will after following her.

Earyn McGee, she runs a kind of a game called Find That Lizard and shares a lot of things about reptiles and there's another word that I don't know, like herps or something.

And Jaida Elcock, who does shark sciences. She's also one of the founders of Minorities in Shark Sciences, they're called MISS for short.

And there's many others. Those are three that if you're thinking about following on social media, I would highly recommend it. I mean, they just bring these species to life in new, interesting, engaging ways. I think we can all really learn from or bring them into the conversation and think about how do we translate this into conservation actions.

Here's Yin Yin:

Yin Yin: Yeah, that's a good question. I'm very excited to answer as well. And then in this case, for the first one, what is an idea I'd like to see is: the community inclusiveness. Like, community and then people can recognize community. That's one unsing idea.

And then another one is who is unsung hero. That is, I would say like in marine conservation like fishermen are unsung hero. They should get more recognition in the field, because they know more about like fishing, or even dolphins – they know more about that.

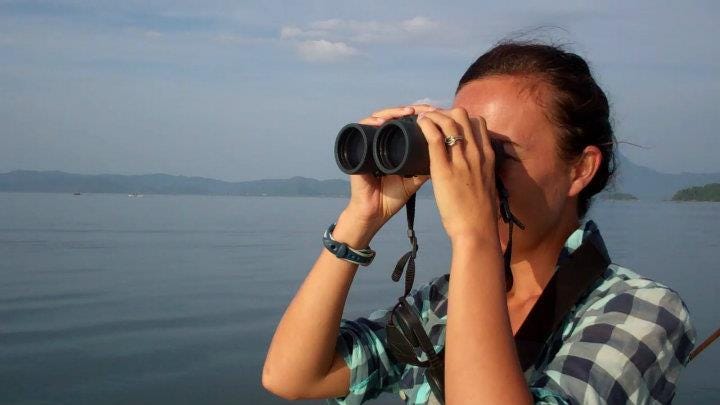

Even though we have, like, technical skills and then going to the boat, going to the sea on a boat, and then taking on several roles as researchers – one sighting, they sighted first. “There, there!” and then they make fun of us. “You guys are on a binocular and then watching everything and then you don't see,” you know? They know the movement, all the movement in the sea. Okay, this in the water, what could this be? And then if they see the flash, what would that be? And then they know – they're experts.

They are also experts in like solving this problem, conservation issue, right?

And then go back to the unsung idea, I would say to be immersed in the community and trying to understand their perspective, and motivate them to speak out about the conservation idea and issue. I will say that.

To give example: when I was starting working in marine mammal research and engage the community, and I can see they are very shy to answer the questions, and then they rejected to go to the questions, you know. But now, when I go back with an ocean backpack [for research trips], they call, “Hey, are you going back?”

And I was really, really happy to that from that situation from like, avoiding us situation from avoiding us and then like, call us communicate us, you know?

I can see that. And then where did that come from? That comes from immersing in their life, because for the last two years I was on the boat with them to immerse in their activities, to do the opportunistic boat surveys because we couldn't do the formal boat surveys [during the pandemic and early coup times]. I asked them: can I follow with this boat to observe the dolphins? And then they accepted, and then in the boat I saw what they do.

And then with these activities I’d wanted to do, I’d been like: why don't they can't take the phone? Because we always ask them, okay, take your phone to the sea and take a picture, and then if you get a capture the picture of the dolphin, you can send it to us. And then they said, “No, we can't take a phone there.” And I thought – I had a bias - why don't they can't take? Because I give them a plastic waterproof pack bag, and and then even I give them that, why don't they? I don't believe that they can’t.

But when I look at that situation from joining them on the boats, I know how much difficult work they have to do, because they have to grab the buoy in very, very fast speed, and then they like harvest fish. And then this phone can, like, any time it can drop. And I understood that: oh that's why they say they can't take phone.

And then we have a lot of conversation there, and then I know they are not shy. They really want to express their voice their experience. They want to talk. They want they really wants to communicate to me their experience on the sea and with the dolphins. And I was really surprised and amazed that, okay, I got a lot of good information and heard their voice. I start to build trust with them, like since then: immersion. That's why I say immerse in the community is an excellent idea, right? And immersion with them and understanding them and communicating with them. That's, that's this really powerful one.

T: Yeah, I think that's really important, Yin Yin. For me – you know, in Myanmar, I never got to be particularly good at the language – but the time I've spent in communities, especially in the Philippines, where I did speak the language a little more and was able to spend more time in the villages, just hanging out in the village was so important in shaping how I view conservation, like how conservation works in the real world.

I think that's a really important idea. In Myanmar, at some of the higher-level meetings I used to join, I would see some “experts” with a lot of official formal background and certifications they would speak very disrespectfully about the communities, actually. They'd say: “they're very simple, they don't understand this, you know they're ignorant.”

I'm glad that there are groups like MCCL, for example, who have this strong belief and practice of immersing themselves in the communities.

And this is what Thanda had to say:

Thanda: I mean, I come across a lot of community, like, leaders – not actual leaders, but like, you know, informal leaders – that I wish they had a lot more capabilities and support. They are the ones who are going to make a much larger difference than people who are getting paid to do the job in organizations. And there's a lot of them.

It's not just young people who want to learn. There are people in communities who actually really want to make their communities better and look after the ocean. I think the way big organizations are set up tend to overlook a lot of these. Not overlook, but I don't see inclusion so much.

Here's Ruth's response:

Ruth: We've talked a lot about emotions in this conversation. So I think it would be more recognition for work, or awareness that there is actually work, on the connection and the relationships between emotions, power, and environmental conflict. So there's a field, the field of emotional political ecology, and I have a colleague, for example, whose work is fantastic, Marien González-Hidalgo, who works directly in that field of emotional political ecology.

And I think those relationships between emotions, power and kind of environment and environmental conflict in particular, that would be something that I think would be worth giving more kind of prevalence to. Again, utterly complicating the picture, but I think it's something really, really important.

T: That's so cool! I've never heard of that before. I'll have to look into it.

And from Chris:

Chris: I think this kind of goes back to one of my earlier points, but I just think that communications and marketing and those general domains can really help conservation. The addendum to that is that like, it has to be done effectively. It's really easy to like, you know, fall short on your objectives.

T: I like that addendum.

Here's Lucy and Diana:

Lucy: Yeah, I mean, I was trying… Yeah, I mean, I would probably go with an idea because I could fill an entire hour with some people that I think require recognition. But I mean, I feel like people think when they create a protected area, that that's it: it's protected. And I think there's not really much thought that it's a process, it needs maintenance, it needs updating, it needs constant reinforcement.

And I think that's sort of lost. Recently, I was involved with a group that was proposing: oh, we're going to apply to create more protected areas. And I was like, well, what about the ones we already have that aren't really being protected? You know, I mean, we should be putting our time and energy into those. Because they exist, first of all, so they don't need to be creative, but you know, they're not really protecting things. So I guess it's a theme with me, I guess.

T: Yeah, well, it makes sense. And Diana, sorry if that was a hard question, but do you have an answer too?

Diana: Yeah, for me, that would be the eDNA. It’s not so recognized, but if we can use it more in Senegal, that would be great. To train more people, to make people know about it.

T: I'm such a dunce when it comes to genetics, but I recognize the power of it. But also, yeah, you need to have people trained in it. You need to have ways to get the samples to the facilities. There's a lot of power to it.

And this is what Rishi had to say:

Rishi: So although this is a conservation pod, I think I would like to shout out a friend and colleague and person that I admire who's not in the field of conservation, but is a land and water defender. Her name is Charlotte Grubb. She is an incredible organizer that has worked with myself on the lithium work in Chile and Argentina, on the film with Honor the Earth, on stopping like Line 3 Pipeline on Dakota Access.

She is an incredible human being who is, I think, one of the most unsung people and from a public perspective, that I know, because she's so grounded. And in an era of everyone needing to broadcast their work far and wide, she is someone who chooses not to do so, to always keep the focus on doing incredible work on the ground, mutual aid projects of all different kinds, direct actions of all different kinds, of reimagining what it means to be in solidarity and what the future could look like in so many different ways. And because she never shouts herself out, I just wanted to shout out Charlotte. If you have a chance to get her on the podcast, you know, I would highly recommend it.

T:It sounds like she's busy saving the world. That would be amazing! I need to learn more about her for sure. And I would say, I would say like, that might not fall under some people's definition of conservation, but it should, right?

Here’s Jean’s response.

Jean: I couldn't come up with an idea, because there's too many and I couldn't filter them out. Unsung hero: I joked last night that it would have to be Mark de la Paz. Like, I don't know why. It was like totally random. I thought of Mark. So he's a marine mammal researcher. I know you're like, you have three Filipinos already lined up for your podcast…

T: He's the third one!

Jean: Oh, okay! Yeah, Mark deserves some recognition, definitely, for the work that he's done on Irrawaddy dolphins, particularly on the critically endangered subpopulation in Iloilo and Guimaras Straits.

T: I agree with that. He's so modest about it, too, so maybe I'll embarrass him when I talk to him by telling him this.

And speaking of Mark, here's Mark:

Mark: Unsung hero. Well, for me, I really look up to Danielle Kreb. She's not known in the Philippines, but I want more people to know about what kind of work she does. So that's something that I want to emulate as well. She's not just doing Irrawaddy dolphins, she's also doing a lot of biodiversity stuff in Indonesia. So I think she deserves more recognition than she does with her kind of work. So Danielle Kreb is my idol.

T: I 100% agree. I feel really lucky that I was able to to work at her field site.And she was so generous in so many ways.

M: Very helpful.

T: I mean, even to the point of bringing me to the immigration office so I could finish getting my research permit…

M: See? She will help you.

T: Even on her own motorbike, and helping me find a place to convince to take passport photos, because the immigration office suddenly wanted a different dimension of photo than the one they listed. And then helping me fill out the forms. You know, she's just such an amazing person. So I second your unsung hero.

M: Yeah, and she's this white girl in Indonesia, right? But she really speaks the language and she's really part of that culture.

T: She's a good example of if you're a foreigner going to do work in another country, that's, that's a good way to do it.

M: Who's really immersed in what she's doing. I mean, she's not the parachute scientist, right? Definitely not. She parachuted and she stayed.

T: And good things happened!

And moving on to the third and last question: What is one of your top pieces of advice for aspiring or younger conservationists?

Jom: This is something I said, but more like specifically relating to colonial science and colonial mentality. Basically, I said that colonial science and colonial mentality are quite tricky and difficult to deal with. I think if we speak up and talk and share about our work, our accomplishments, others will know that there is a lot of marine mammal research being done in our country, research being done by locals, that we have the local expertise. And in many ways, we can do things or have done things that no one else has.

And then especially to young researchers, you should take the opportunity, talk about your work, to showcase all the good things, all the science that is being done, and lead when you can. Step up and believe that you don't have to be educated in the US or abroad to be able to do good science.

That was Joan. And now Brooke's response:

Brooke: Well, we touched on the one before in terms of additional skills to acquire. So I would say add project management skills to your list.

A big piece of advice I want to offer is that we can't effectively take care of the planet if we don't take care of ourselves. Especially for young, early career conservationists, you have many years ahead of you working on this. And I think the key to that personal sustainability is to set boundaries, practice self-care, and I'll admit it is a practice. So it's constantly constant muscle you have to like hone and flex and don't stay in toxic work environments.There's other places where you can do your work that'll treat you better. I mean, we're out here saving the world - we should do it in a healthy, supportive environment!

And back to what we were talking about earlier of how emotionally invested we get: sometimes that can work against us as well, is that we feel like we can't make that change, or, you know, leave that team because we're so emotionally invested, but we have to set those boundaries that it still has to be healthy for me. I can still have a life outside of this job.

And practice what I need to practice to take care of myself. We need everyone showing up as their best selves, whatever that means for that day. But we can only do that if we take care of ourselves.

And Yin Yin’s answer:

Yin Yin: Yeah, my piece of advice to the younger conservationists is whenever they are doing their work, don't use people or community as runway for your own benefit... I don't know if you can understand or not, but in Burmese I can explain it well…

So, runway, this is road, right? Just communicate with them and then trying to understand each other, and don't use people for our own benefit.

T: So I think it's kind of similar to like, don't use them as, we could say, like pawns in a game of chess. Don't just use them for your own ideas. You have to respect them and open up and collaborate instead of trying to manipulate or control them.

Yin Yin: And another piece of advice could be like communicate with them with with heart and love. And then you will know the feeling of feeling the sun from both sides, you know. Heart and love.

T: Yeah, that's really nice, Yin Yin.

And this is what Thanda had to say:

Thanda: Don't doubt yourself, just do it. Like, I would imagine everybody still struggle with the impact they're having. And, you know, but just, just, just do it.

I mean, it wasn't in my five year plans to start a conservation organization.

But I do look back, because I have a habit of writing a very extensive to-do list and my thoughts. If I get really anxious, I will write down all my thoughts to just see it visually. But I feel like I never had any plans to do this.

But also, because I had been leading up to it, I had been volunteering for different organizations, and I knew it was something I was passionate about. I don't know if that's the right word. But if I was honest with myself, I would have always known this is what I want. This is what I wanted to do. It wouldn't have just fallen on my lap.

And I joke about how I still have screenshots in my phone of my first expedition and I'm like, “Shit, I am doing this now, I don't know what I'm doing?” and so I Googled “how to run an NGO” and I found one good article and I thought, okay, I'm gonna lose internet so I'm gonna take screenshots of this article to read on the journey.

I haven't read it, but I just don't think it's gonna apply to where I am now. But I still sort of hang on to it, like a reminder of, I suppose, how far I've come.

I mean, traditionally, people would say, in Myanmar, that I'm not a marine biologist. People who likes to hold on to titles will never give me the space. I'm not somebody's, you know, son or daughter or position, they would they would or not from the army, so to speak, they would not give me that space to listen. But I managed to put my foot down and I’m still here.

So if you have the opportunity to do something and you’re in the position to do that one thing, then do it.1

This is Ruth's response:

Ruth: I would say, and this is not necessarily per se to do with conservation, which might be surprising for someone who described themselves as a conservationist, but I would say: really really work on your listening skills, on communication skills, on your emotional self-awareness, emotional awareness, emotional intelligence. Because that's fundamental to this kind of work, absolutely fundamental to this kind of work, because it's all about, the foundation is relationship building. It's crucial.

And also related to that is: think about and actively look for those opportunities where you can interface with the policy environment, because that's how you can have an impact. That's how you can start to shape things. That's how you can kind of feed your ideas into places where they may, they may not, but they may have, you may can drop seeds where they may actually flourish and have an impact.

And to build those bridges and to build those relationships and to be a bridge to those marginalized voices (I mean both human and the more-than-human world). So that would be my response.

And Chris's response:

Chris: I would say, find your home. Find wherever home is.

Here's Lucy and Diana:

Diana: For me, it's just to call Senegalese women to get involved because we are the relief. Yeah, for me, it's the advice that I'm going to give to people here, young people.

Lucy: Because what?

Diana: Because we are the relief after the relief.

Lucy: I'm not sure I understand the context, though.

Diana: Because tomorrow… we are the young researchers

Lucy: Ah! You are the ones, you’re the future generation!

Diana: So we need to start now, to start learning a lot of stuff now. And then in the future, we'll be able to do stuff.

Lucy: You'll be leaders.

T: Yeah, I love that.

Lucy: That's true. Anything to do with nature here, there are not many women involved. Like if you look at the rangers in the marine protected areas, if you look at the fishing community, obviously it's all men. But women care about nature and I think that's a great piece of advice.

Mine is really: I know there's a lot of people out there with enthusiasm and I don't want them to give up. Don't give up if at first you don't succeed, because it is really hard. And I think, you know, unfortunately that's the reality. I mean, it was, it was hard for me and I grew up in America, you know, so it's never going to be easy to get into a conservation career.

But if you really care, just keep at it and keep looking for creative ways to do something. You know, it might not be what you originally intended to do, but you know, you might find something else.

I mean, I was going to be a wolf biologist, by the way. That was going to be the thing. It just so happened that after college, I went out to San Francisco with some friends and started volunteering at the California Marine Mammal Center and fell madly in love with seals. And that was it. You know, I said, Okay, I want to do something with the ocean. And so, you know, it's still animals, it's still wildlife, but it's not what the original thing was.

But I feel like there’s so much that we all need to be doing. The Earth is really degrading, the marine system is really degrading – we need more people. And if you really care, then don’t let anything stop you – just keep trying until you find a way. That’s my advice.

Here’s what Rishi had to say:

Rishi: Just build your community early and often. Not even just as academics, just as people in this country, I don't think we're encouraged enough to build the community that will help us flourish in this world. I think we're so taught that individual accolades are the accolades that matter most.

And it's so hard to do transformative work outside of an individualistic capitalistic framing if you don't have that community. It's actually impossible. So I guess one thing would just be be very intentional about creating a community of people that will help you thrive no matter where you go.

And then I guess another thing is just that disciplinary boundaries, much like the distinction of basic research versus applied research, are gray areas that you should feel very free to trample on early and often and whenever it makes sense. And just to remember that, you know, we're all like taught in boxes out of convenience and not out of how reality in the world is reflected.

So embrace the complexity of all the things that don't make sense and then go dance in it. Because, you know, that is where the interesting work happens. And it is how the world really works.

And don't get so caught up in your disciplinary expertise that you won't engage in something new and take that mindset of like, “I have no idea what's going on in this weird space, this is not how my disciplinary training taught me to think about this problem, but I can learn and I can learn because I have a community of people around me that will help me learn and will be giving me grace when I fail.”

T: That's so important.

Here are wise words from Jean:

Jean: This one should be easy, supposedly. Find a good mentor, preferably one that isn't afraid to challenge the status quo. I think it sounds “easy,” but they're out there. You might have to look a while, but they're out there.

T: That is really important. I mean, my PhD advisor was amazing. She's still very important in my life years later. And she's, you know, a seabird and marine mammal expert, doesn't do any social science work, but she was willing to challenge status quo because she's like, “I know this work needs to be done, and I'm happy to have my students do it.” And so, yeah, I agree. That's a really good piece of advice.

And our last response for this compilation is from Mark:

Mark: You have to have that passion. You have to know what you're going to work with. So you have to love and understand what you're trying to conserve. Because often it's going to be very challenging and unrewarding.

There are ways to make it fun… I know you talk about it, and I really relate to you to be like that “grumpy lady” [laughs] - I think we've been jaded so much, but because of that passion, that's what's keeping me going, keeping me attached to this kind of sometimes ungrateful work.

So yeah, it's not going to be easy. It's not going to be easy, but it's the passion that keeps me on the go.

And there you have it.

That is a wrap to the Conservation Expert interviews for this season.

I hope and plan to have a brief interview with my amazing brother, Danny Whitty. He is a non-speaking autistic writer and advocate on his thoughts of how the realms of disability justice and conservation overlap and have similarities. I know he has some brilliant thoughts on it because we've chatted about it before several times. Unfortunately, as is the case with many folks with his disability, when his body is having a tough time, it's quite unpredictable what he'll be able to do, what energy he'll be able to spend.

So I'm still hopeful that by the end of the year, I'll be able to get some thoughts from him. Otherwise, I will just have another brief monologue to wrap up this first season. And I have quite a few brief but important thoughts to share there.

Thank you so much for listening along. And again, any support you can offer in terms of liking and reviewing wherever you get your podcasts, commenting, starting discussions on the Substack site, even donating (and again, thank you so much to those who have generously donated so far - all that information is on the Substack site).

I really appreciate being able to share these ideas with you. Thank you so much for joining. Take care!

Share this post