Transcript:

Welcome to Episode 2! I truly appreciate the kind feedback you've shared with me already, and I am very excited to share this first interview of the podcast.

I spoke with Dr. Jo Marie Acebes, known as Jom. She's a good friend who I've gotten to know over the years through the wonderful Southeast Asia Marine Mammal research community, and more specifically as part of the fantastic family of marine mammal researchers working in the Philippines.

She is the Founder and Principal Investigator of BALYENA.ORG, a non-profit organization with a mission to support the conservation of whales, dolphins, and their natural habitats in the Philippines. They do work on research, education, and capacity-building, including their work on humpback whales - currently the longest-running cetacean (whales, dolphins, porpoises) research project in the country. I encourage you to check out the episode notes for a more complete biography, because it is impressive, including a doctorate in veterinary medicine as well as marine environmental history. Until recently, she was a Senior Museum Researcher at the National Museum of the Philippines. And she is a National Geographic Explorer, Fulbright Scholar, and member of the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group, the IUCN Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force, and the Philippine Aquatic Red List Committee – Subcommittee on Cetaceans and Subcommittee on Elasmobranchs.

I so enjoy and appreciate the time I get to spend with Jom at various conferences and workshops. She's one of the folks I particularly look forward to chatting with during coffee breaks and meals out during conferences - I know it will always be a very real and thoughtful conversation. And that really encapsulates part of what I want to bring to this podcast: those side conversations at conferences that have really taught me more than the actual presentations themselves.

[MUSIC BREAK]

Again, that is music by Soe Moe Thwin, Zyan Htet, and Min Min in Myanmar - the whole song is at the end of the episode. I really love this song; Soe Moe Thwin is starting a career in music and I'm so glad I can share this song here and I encourage you to check out his YouTube page.

Here's some context before we dive in:

(1) We talk quite about about publications here. If you're not a professional in the field, perhaps that seems a bit tangential to the "adventurous" work of "saving the world," but it's actually fairly important (more than it should be). Peer-reviewed publications were once described to me by a professor as "currency." They are the accepted evidence of your expertise. And so, when a researcher or conservation organization is applying for funding for their work, they are often asked to provide evidence of their qualifications. So, your publication record is linked to your ability to drum up money for your continued work.

Authorship in publications is a fraught issue, as many of you know all too well. It's basically who gets credit for the work done. But the publication is really a relatively small end-product of a large amount of concerted effort, and it demonstrates the time and resources you have to write up and submit (and revise and resubmit) an article written in stuffy academic English. These skills are really only tangential, in the grand scheme of things, to one's ability to conduct good research and to carry out good conservation work.

Authorship is also how one gets "famous" in academic circles. That recognition as an expert also plays into the opportunities that are afforded to you and the platforms that you have access to, with implications for inclusion and diversity in the field.

(2) We also discuss permits for research. If you're poking around nature for research, especially if it's a threatened species or in a conservation area, you will quite possibly need a permit for various types of activities. Yes, it can be a bureaucratic hassle. But it exists for a good reason: to monitor activities that might have an impact on ecosystems and people. And if you're a foreign researcher, you are a guest in whatever country you're working in - and you need to follow the rules.

(3) Jom references two of our highly esteemed colleagues: Bill Perrin, a pioneer in marine mammal research including in Southeast Asia, and Edna Sabater, one of the leading active researchers of marine mammals in the Philippines. Sadly, Bill passed away last year; he left a huge and meaningful legacy, one that is very much felt among the research community in Southeast Asia. You'll notice in Jom's references to him that he was very much a straight talker.

And with that - let's go!

Tara: I'm always afraid I'm going to talk with someone for a while and then realize I haven't pressed record! You're actually the first interview I'm doing for this.

Jom: Oh! Okay! Although I might end up ranting more than anything.

T: Ranting is good!

And, funnily, I called this Conservation Realist, and I initially thought, "I could just call it CR for short." And then I was like, "No."

J: [laughs] Not here, it's not going to sound nice!

T: Not in the Philippines! I should've chosen a different name, had I thought about that ahead of time.

Narrator: For those who are not familiar with the Philippines, CR is the acronym for "Comfort Room," also known as the toilets or bathroom.

T: You know, parachute science, it's kind of funny for me to be asking you about this because I am a foreigner who has only worked in other countries. And I'm sure I've made my share of missteps. But I have such high regard for my colleagues who are working locally in their own countries and regions. So I appreciate you being willing maybe to educate me or others a little more about your experiences with it and your perspectives on it.

J: When people ask me about parachute science, I tend to say that it's not the usual definition that I'm actually thinking of. When I say "usual definition," you know how Asha de Vos has been cited for defining parachute science: "colonial science or parachute science is the conservation model where researchers from the developed world come to countries like mine [like the Philippines for example], do research, and leave without any investment in human capacity or infrastructure."

It doesn't exactly happen just like that, because it makes it sound very simple: that someone comes in, like a foreign researcher would come in to the Philippines for example, do research, and just leave with all the data. Because for me, if you think of it just like that, it's more focused on collecting specimens - that's usually what people think, at least here in the Philippines. But it's not just that. It's a lot more complicated, and it has a lot more repercussions.

So, the way I think of it: it's very closely tied up to the other term, "colonial science." I think that's more broad and encompassing, because that ties up to something that we're more familiar with here in the Philippines, which is the idea of colonial mentality. Colonial mentality is mainly... I think this became very popular in the 80s, in the Philippines at least, during my generation. This is when someone just thinks anything foreign, or American specifically for us, is good. And if it's Filipino, it's not good. So it's like extreme opposites: American or anything foreign, always good, nothing bad, but when it's Filipino, it's low quality. It doesn't have to be just a product, but it could be anything, like an idea. So I think they're tied together.

If I go back to my own experience, I would say that my very first experience of parachute or colonial science was when I was involved in this huge collaborative project on humpback whales. And of course, being a newbie knowing nothing and nobody, naturally you feel, "Oh, I'm so excited, I'm working with all these big people, I'd really like to learn about everything humpback!" And so you're very generous with information and data. And basically I ended up sharing all of our data, including samples, tissue samples and all that.

Then in the end, I found out during a conference that they already had results based on the samples that we got and contributed, and that they were already presenting it at the conference. And we didn't even know about it. So that was my very first experience, and I didn't even realize that could happen. So being naive and everything, I was like, "Oh... they can actually do that!" Without telling you, they'll present it.

And what made it was worse was that they actually found something very, very interesting, but they didn't even share it to us. I didn't find out until I was sitting at the conference and listening to the talk. And then they published that, obviously. No acknowledgement whatsoever. Actually, during that time I remember, I wasn't even looking for *my* name. I was just waiting for the recognition - at the time, I was still with WWF-Philippines - that they should at least acknowledge that these were from samples taken by us. But there was none.

Of course there were so many excuses given. But I do give credit to the people that, in the end, they did try to make amends for it. But it was a terrible experience for someone very new in the field. So I think that's more the classic parachute science: literally, without even having to come to the country, because I literally gave them all the data. No recognition, nothing whatsoever.

But that's the classic one. I think my succeeding experiences (sadly, there were more examples) were even worse. And that I think there's a type that is not normally talked about, mainly because it also involves Filipinos doing the same thing to their fellow Filipinos. That's where the colonial mentality comes in. Fellow Filipinos would think, "Oh, because they were foreign, they were educated in the US or Australia or wherever, so they know better. But you're Filipino, so why should I believe you?"

Even if there are more Filipinos studying Irrawaddy dolphins, let's say, and then someone comes in, just literally comes in and writes a proposal and gets granted a proposal to work on a project on a species in your country without really involving the people who have been working on that species for many years. And then, in the end, they'll get all the credit for it, because they're the grant proponent or project proponent.

The other one is publications, and I guess it all boils down to that, sadly, because grant-giving institutions at least do look at that. You know when you apply for a grant and you're asked, "have you done any work on this species?" or how can you prove that you've done this work, then you have to cite your publications. So the most recent experience I've had is that we helped a foreign researcher set up in the Philippines. We did all the groundwork basically, because they don't speak an ounce of Filipino, so we did all the groundwork, and all the boat crew people, talked to all the government officials. You know how it works here in the Philippines, you have to get permission for everything, so obviously we the Filipinos did all that. We also helped conceptualize the project, how to do the surveys, etc. And then, in the end, we find out years later that they actually wrote a paper and it was about to be published.

How did we find out... it was through Edna, actually. You how you can get email updates about papers about to come out - it's been submitted, but hasn't been published yet - so someone got a notification of that. And we saw that of these authors, none of them are Filipino. And the data is exactly the same data that we collected for another project. The main author wasn't even there at the beginning of the project - she was there toward the end, but she got a hold of all the data from the very beginning.

So that started the whole drama. If we hadn't flagged it with the Editor-in-Chief...but even the Editor-in-Chief of the journal - which I think also plays a huge role, like journals definitely have a huge role to play when it comes to preventing parachute or colonial science - they didn't even acknowledge the first email. It took my other colleague, who was Canadian, emailing the same editor, then he replied, saying basically, "Oh we can't do anything about that because we don't know about the fieldwork, so you should contact directly the primary authors."

And it took weeks and it's still not resolved, to be honest. But it did stop them from publishing it because we flagged it. But the bad part about that is even the main author still refuses to acknowledge that our contribution - the Filipinos' - is worth co-authorship. She did in the end offer, oh, if you'd like to review this paper, then we can revise and resubmit, basically. But just the fact that she refused to acknowledge and even apologize, to me that's just unacceptable. I really want her to first admit that what she did was wrong, and that she has to admit that her notions of what constitutes co-authorship is just wrong. Because she's basically saying, "Oh, they just did the fieldwork." But she wasn't even there in the beginning.

T: Gosh, yeah. I mean, I'm a little familiar, having watched from the sidelines of this particular drama. As for definitions for co-authorship, there are different ways that people define it and different ways that people are trained to view it, which is a problem, because everyone's coming at it with a different understanding. So maybe I could understand a bit of leeway there.

But what I really couldn't understand was them absolutely not contacting any of you. And it really detracted from the quality of their work. You Filipino researchers have been doing amazing work in that area. I don't understand why someone would not choose to include that in their study in a more collaborative way. I was just so baffled and really shocked by that whole situation.

J: Unfortunately, there's more of that that has happened, it's just nobody noticed. Actually, when that happened, it prompted me to look back at other papers that they wrote, and I found out, "Oh wait, this is also the project that we worked on," and obviously they didn't include us. And no Filipino listed there. And I don't believe it, that they're able to do that work without a single Filipino helping. So it's ridiculous, but they get away with it.

And that brings me to the point that that's why the whole colonial mentality idea plays a big role there, because the Filipinos allow it happen. Because they think, "Oh yeah, they did all the work, they're the ones who can write in English, so they should be the authors."

And even the permitting system! That's another thing. A typical Filipino researcher, if you're honest, would have to go through all these steps just to get a permit to collect a specimen. Perfect example there is Edna. It took her years to get a permit to collect biopsy samples for whales. She had to go to each municipality around the Bohol Sea to get them to approve it before it's actually submitted to the government agency.

But there's another foreign group that just takes a sample, then take it back. That's 2 things they're doing illegally: taking a sample even if it's just a byproduct of a protected species, that's one violation (without a permit, I mean), and then taking it out of the country - that's illegal, too. You can't just take out samples like that without permission. But they were able to do it. And they got it published, too.

T: Oh my gosh. I had to get approval from Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (entity overseeing environmental research in the province where I worked) and all the barangays (villages) where I worked - I went through the process. And as someone who went through that process, even though I'm not a local researcher, that irks me so much. Just the arrogance of going in and doing that, especially with samples. That's the highest level of protection that requires permits. I just find that so appalling.

J: And then, for me personally, what made it worse: I notified the Bureau of Fisheries. I told them exactly what happened. And they just shrugged it off. And I was like, "If that was me, are you going to shrug it off? I'm sure you're not. You're going to fine me and say 'Oh what you did is illegal'." But because they're foreign, they just let it go. "Oh well, we'll catch them next time."

T: It's almost like - I'm sure there's a well-formulated term for this - internalized colonial viewpoint that privileges what external actors (certain external actors) do and their skills.

J: It's not entirely the foreigners' fault. I have to give the benefit of the doubt to some who may not know that those are the rules. But that would be the responsibility of whoever is leading them or took them on on the project to tell them what the laws are in the public.

T: But you know, I bet they wouldn't try to do that if it was Americans doing work in Europe or Australia, right?

So I like how you started with a more simple definition of parachute science: the way it's written there, it's like an isolated occurrence - the researcher comes in, collects stuff, goes out, and gets recognition for their work. But really as you've experienced it, it's not isolated - it's intertwined with local researchers, local organizations who are working extremely hard and doing good work. And it affects you and your colleagues there negatively in so many ways, so it's not like this abstract, victimless act. It is really taking away from people who are on the ground and really dedicating their careers, their lives to this work.

J: Yeah, and I forgot to mention: "taking over" - those are the key words. It's the taking over of a project, of something that's already been started by a local. It's almost deceiving at the beginning - it sounds great, that "Oh, we'd like to collaborate with you." But in the end, it's "we're going to take over the project, and you'll be forgotten, literally, and it's going to be OUR project, something that WE did." And it's just bullshit!

T: And they get to be the intrepid explorers going to a different country and saving nature there. I also want to add that the Philippines is one of the most dangerous countries for people doing environmental work, and especially the risk is much higher (that's my understanding) for local researchers and activists. So it has that added element: these researchers and activists are putting so much on the line, and being disrespected like that is like... adding insult to injury (...that's not the right turn of phrase, but you know what I mean!).

J: I know! And that whole taking over... I realized how powerful their words are against yours. It's going to sound like I'm being arrogant or waiting for recognition, but it just the fact that it makes it sound like they did that work, and started all the work, and "who are you?". Basically, it's like that.

And this is in the international realm. Locals might know what you've done, but when you go out there: the only names they've heard are the names of the foreign researchers. It's like, "Oh, you did work on that, really? I thought it was this group." It's messed up, to be honest.

T: To say the least! Do you have any thoughts on why this happens? Do you think it's just ignorance, like a lack of mindfulness on the part of these foreign researchers?

J: It's hard to generalize, I guess. Like for example, for my earlier experience, I think it's mainly ignorance. They didn't know (1) that it was that important (although Bill would disagree!) to recognize you for... they thought it was valid to say, "Oh we already have like 100 co-authors, we couldn't include you anymore," but according to Bill, that's bullshit. But also, for example, not informing you about the result - maybe, okay, maybe there was a lapse there that they really did forget to email you to let you know, "Oh, by the way, we're presenting this, and it's really cool, and we're presenting it at the conference." Maybe.

But for others... hmm. It's hard to say. But I'm judging them. Because I can't think of a reason why they would do it. And it still makes me wonder why they did it. The whole taking over, for example, not giving you credit, refusing to acknowledge any involvement... unfortunately, I can't explain it. Maybe...yeah, I can't even say "maybe" anymore.

T: And how does it feel for you - obviously, you're voicing a lot of frustration at this disrespect and lack of acknowledgment - but more personally, how does it feel to you whenever this happens to you or one of your close friends and colleagues?

J: First, it's very exhausting. It's exhausting because it just keeps happening. I guess now that I'm older, I'm more trying to make sure that they don't get away with it when they're doing it to someone else. But it's really exhausting because it takes a lot of energy. Even just having to flag it with the editors, or just asking people involved in the project that didn't involve a local. It's not my responsibility any more, but I feel like I should do something about it. Because if you don't, the younger Filipinos might not even know that they should actually fight for it. Generally, it's that: it's exhausting and frustrating.

And it does make you angry, at some point. Mainly because we all know that getting recognition for any project or any work or any publication, it all boils down to getting funding, which is already very competitive. To add that as another obstacle is just too much. And as you said, we do face other obstacles on the ground, politically and socially. So to add that to all we have to deal with interferes with the real work.

T: Yeah, a lot of you are running organizations on a shoestring. You're not based at universities with high salaries (I'm not saying that's the only source of parachute science, I know that's not true), and that discrepancy between the financial safety net of who's doing the parachute science and who are the local scientists who are suffering because of it, makes the problem that much more problematic to me.

When I've been guiding young researchers in Myanmar, I feel like I've been almost paranoid at times. Like, "When you're emailing someone with an idea, CC someone else like a neutral 3rd party." I feel like I'm training them to be paranoid, and sometimes I have to take a step back - am I just teaching them that everyone is out to steal their ideas? But it's with good reason: I want them to get credit for the work that they're doing, for their ideas. I don't want them to be taken advantage of, whether it's through ignorance or more blatant disrespect. So listening to your experiences kind of makes me feel like I haven't been too extreme in what I've been instructing them to do.

J: It's true. I feel the same way now, having experienced all of that, when a younger researcher comes up to me: "You should have a signed agreement. Before you get involved in this project, you have to have a signed agreement clearly state who gets to do what and what credit is given to whom." Because you never know. You'll be lucky if you always deal with honest, great people, but there are unfortunately bad people out there.

T: So my next question - you can feel free to tell me to skip it, because it is asking you for suggestions, when really the burden should be on foreigners to think about this deeply - but what are some things that foreign researchers could do better to avoid being parachuters?

J: I guess, I make it sound like it's just common sense. Because if I were going to go to a different country, like, say, Australia. I can't just go and start something without finding out first who is doing the work on what, what permissions I need to be able to do anything. So basically it's just doing your homework before you even start planning to do any project outside of your own country, and not assuming that you know how it works, because you probably don't. So get good contacts locally. Be honest on what your intentions are. Say what you intend to do, and then find out if there's room for any collaboration. Be very open to what the locals are saying, and do not take credit for something that you didn't do.

T: I think humility is a big part of that, too. Just because a country is cheaper than the country you live in, maybe the rules are more lax, it doesn't mean that it's your playground.

J: That was one thing that I forgot to mention. I think some researchers have a notion of, for example, the Philippines, which is also known for corruption. So there's that notion that everyone is corrupt, so why bother following the rules?

And also, I head this - it's true, it's been fed - that "Oh, Filipino researchers can't write. So they never write up. They do all the fieldwork, but they don't write up reports or publish." That really makes me very upset. They don't know the working conditions that we're in, whether in academia or NGOs. Unlike the set-up in academia in the US or Australia, or even in NGOs there, we don't get paid to do research and write it up. Especially if you're teaching. In most cases, for you to be able to do any fieldwork is rare. If you have huge funding for a project tied up to the university, then you're lucky. Then you actually have the time to do the fieldwork and write it up. But still, that is not your priority, and you have other work to do. That is the main reason why a lot of the fieldwork that has been done... well, they must have submitted reports because that's required... but there are so many other obstacles when it comes to publishing. That should never be made the gauge of how well you do your work, because unfortunately it's not that way in the Philippines. Publishing is a luxury. No one has enough time or the money - because most of the time you have to pay - to be able to publish. We've been told that: "Filipinos can't write. They do all the fieldwork, but can't publish."

T: That's so insulting, and such a lazy excuse. Even if it were true, which I know it's not, the response would be: "Let's invest in supporting skills for writing." I hear that kind of lazy excuse a lot when it comes to increasing diversity and inclusion in the field. It's just like, well, things are this way, so we'll just continue the way we're going, instead of: let's investigate how to systemically change the barriers to true diversity and inclusion.

So my last question on this topic: what do you think has to change, on a systemic level? You've touched on some points already, like accountability from journals.

J: There are already guidelines from publishers on how authorship should be defined, but those are just guidelines and it still depends on the journals to follow them. That's one.

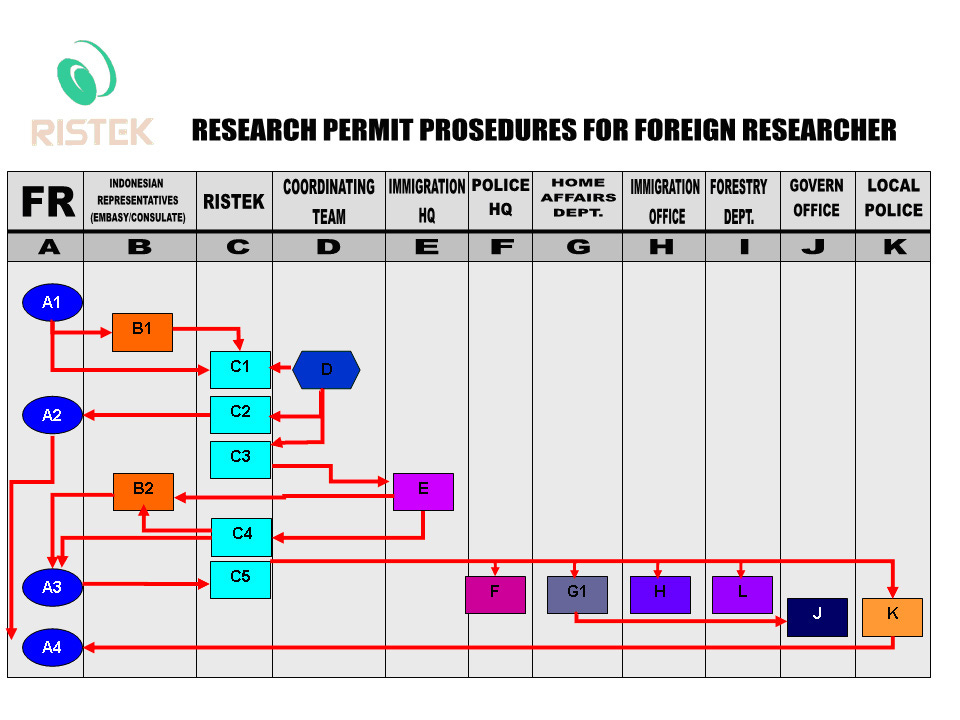

I've been thinking for a long time that I wish the Philippines was a lot more strict, like Indonesia. In Indonesia, you need a research permit to even enter the country, and when you're doing your PhD thesis, you have to present and you have to partner with a local collaborator. They have to give the "go" signal to your project proposal before you're even given a research visa. I've heard of someone whose visa was revoked because basically he did something wrong, and he could never go back to Indonesia. And I was thinking, I wish the Philippines were like that. Because that's one way to limit people who just come in and leave without involving locals and without authorities knowing what they're actually doing. I think it's a huge step and I think it will make parachute science a lot less of a problem.

T: As someone who went through the Indonesia process - I feel like it's more streamlined since then, since this was over ten years ago - it was like a scavenger hunt. But it was good. It was a lot, but it was clearly outlined. I had really great local collaborators who helped me a lot. And once it was done, it was done - I could do my work. It was a lot, but it was reasonable. I try to be mindful about this anyway, but I could see how this really would prompt someone to be very mindful: you have to share your data, you have to report back. So I'm with you.

J: Just need to get a politician to pass this law.

T: Good luck with that! But I hope it happens. Do you feel like this internalized colonial viewpoint is changing with younger generations of researchers and conservationists?

J: I think it has been changing. Unfortunately, in marine mammal science, there are very few younger people, which is sad - I hope that changes soon. The younger generation are a lot more confident about their work, which is good. I think that also has a role to play, when you're confident that you're doing the right thing, then you're more confident to say, "Wait a minute. This is my work and I should get credit for it." So the new generation has an advantage when it comes to that. So I guess you can be hopeful that there will be less parachute science, and also more recognition for Filipino work.

T: That's good to hear. Thank you - I learned a lot, Jom. Thank you.

J: Thank you!

So there we have it - another excellent conversation with Jom, made even better because I'm able to share it with you. We actually continued our conversation, but that's for a future episode (sneak peek: it relates to what I call the "human collateral damage" of conservation).

As a reminder: please comment and get some discussions going! And like, share, and (if you have the means and the motivation) donate at the link in the About section. Thank you for being here

For now, you can follow Jom's work via BALYENA.ORG's Instagram and Facebook page. And stay tuned for next week, where I chat with marketing expert Brooke Tully on how conservation marketing campaigns can be conducted more respectfully, responsibly, and effectively.

Thank you, all!

ABOUT DR. JO MARIE ACEBES:

Jom is the Founder and Principal Investigator of a non-profit organization called BALYENA.ORG (on Facebook, Instagram), with a mission to support the conservation of whales and dolphins and their natural habitats in the Philippines through research, education and capacity-building. Jom began her career in research and marine conservation at WWF-Philippines as the Project Leader of the Cetacean Research and Conservation Project in 2000. It was under WWF-Philippines that she started the study on humpback whales in the Babuyan Marine Corridor in the Philippines. After leaving WWF, she continued this research by establishing BALYENA.ORG and it is currently the longest-running, continuous cetacean research in the Philippines. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology from the Ateneo de Manila University, a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine from the University of the Philippines at Los Baños, a Master of Science in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management from the University of Oxford and a PhD in Marine Environmental History from Murdoch University, Perth. Her interests range from marine mammal population biology and conservation, cetacean-human interactions, biodiversity conservation, wildlife medicine, to historical and current fisheries for large marine vertebrates. Her current projects include “Conservation of the Babuyan Marine Corridor: the only breeding ground of humpback whales in the Philippines”, “In Search of Bughaw, the lone blue whale in the Bohol Sea, Philippines”, and “Return of the Rorquals in the Bohol Sea: assessment and monitoring of the blue whale, Bryde’s and Omura’s whales.” She has worked in the both the NGO and government sectors, as well as the academe. Until recently she was a Senior Museum Researcher at the Zoology Division of the National Museum of the Philippines. Jom is a National Geographic Explorer; Fulbright Scholar; member of the IUCN Cetacean Specialist Group; member of the IUCN Marine Mammal Protected Areas Task Force and a member of the Philippine Aquatic Red List Committee – Subcommittee on Cetaceans and Subcommittee on Elasmobranchs.

Share this post