KEY POINTS:

The idea of eco-leadership as an ecosystem-based approach to leadership, and generally, shifting toward more decentralized paradigms of leadership (focusing on the phenomenon of leadership rather than the “hero leader”)

The Inner Development Goals, as a response to the Sustainable Development Goals (I think we should ALL be working on these IDGs!)

The importance of honoring the different perspectives that people bring to the table and establishing common ground by appreciating the differences

How to cultivate the enabling conditions that allow leadership (not necessarily individual leaders) to emerge and thrive?

Introverts and leadership (personally interesting to me!)

“All of us have the potential for a role in leadership.”

We often speak of “leadership” in conservation, and how important “good leadership” is to successful projects (I mean, duh), but I’ve long felt that we need to be digging deeper into what “good leadership” actually is, *and* how to support or cultivate its development. What I’ve read in conservation-focused papers seems to only scratch the surface of a fairly limited idea of leadership, and it doesn’t really provide useful guidelines for how to apply that knowledge in the real world. And then when I’ve searched for resources about leadership from other sectors, the results are generally flooded by resources for business or self-improvement, which are useful in a way, but not quite what I was looking for.

So I was genuinely excited to have this conversation with Dr. Eric Kaufman, an expert in leadership-as-practice at Virginia Tech and associate head of the Department of Agricultural, Leadership, and Community Education there. I met Eric when we were both on a grant review committee together; I appreciated his insights during the committee meetings, and so I continued to follow him from the shadows on LinkedIn – and I learned a lot from what he posted. I truly appreciate his willingness to share his time and energy with us for this podcast, and I learned so much. I’m especially intrigued by the idea of more decentralized paradigms of leadership, as well as the Inner Development Goals, which you’ll hear about.

While editing the audio, I realized: WOW, I talked a LOT during this interview. I was trying to work through some thoughts, because we were talking about something that is fairly new terrain for me, but I hadn’t realized how many words it was taking me to do so! But fret not: Eric still manages to impart a lot of fascinating information, and I think you’ll really enjoy this conversation.

(Some of the ideas we talk about resonate in particular with the interview with Wint Hte from earlier in the year, so I recommend checking that out!)

TRANSCRIPT

Tara: Well, thank you again for your willingness to share your time and expertise with this podcast. It’s a great excuse for me to get to talk to people whose work I want to learn more about. And as I shared in our communication via e-mail: though my background initiated in ecology and then moved toward more interdisciplinary work, even at the very beginning when I was studying monkeys in Thailand, you can, if you’re observing, you can see how important human processes are in the endeavor of conservation. And there are obvious commonalities across other sectors. in areas of work. And one thing that comes up again and again is leadership. And I actually haven’t run into anyone else directly like you who specializes in studying leadership. So I’m excited to learn from you.

Eric: Good. Well, I’m glad to share what I can and offer some insight and maybe help listeners to the podcast connect to some other resources too. That would be great.

T: So could you just share a brief introduction to yourself and your work just to orient everyone?

E: So I’m Eric Kaufman. I’m a professor and extension specialist at Virginia Tech. I’m in a Department of Agricultural Leadership and Community Education. And my background is really on the education side, particularly in the context of agriculture education. I taught high school agri-science for a few years, but then in graduate school focused more on leadership development, particularly in community and volunteer settings. And I have really enjoyed leaning into that and considering how leadership works, generally outside of a lot of work contexts. So there’s literature that focuses on like in the workplace, like what does leadership look like? And some of that bleeds over heavily into management, but my interest is really outside of some of those built-in power dynamics of the workplace. How do people get things done?

And so I’ve been at Virginia Tech since 2007 and have looked at different ways that we can study that. Then at a practical level, working with different groups, thinking about how we engage stakeholders in planning programs and guiding the work and thinking about engaging volunteers and being able to activate people for success in a variety of contexts.

T: That’s really interesting! I’ll share one of my not very charitable entry points to thinking more about leadership and conservation: when I was in graduate school, a paper came out that was led by more ecology folks, but they had also conducted some research on the social side of the communities they were working with. And one of their big findings was that leadership was critically important to success. And though I do believe academia has its place, for me, that was the first inkling where I was like, yeah, of course, leadership is important! What are you doing, people?

But then I also recognize that there is a place for academic study of these phenomenon and processes that seem obvious on the surface, but when you dig down, it’s not really clear: how do you actually study this or how do you actually amplify this on the ground?

So yeah, I’ve always been kind of antsy for conservation folks to look more into like, not just is leadership important, because if you’re working in a place that doesn’t have existing strong leadership, then what do you do? Or how do you engage with existing leadership structures? That, for me, is a big gap that I’ve never seen really addressed in conservation-specific work, though I’m not that familiar with the more agricultural type of work, which I think is ahead of the rest of management and conservation research in a lot of ways.

That was my long-winded way of asking: based on your work, what would you say are some core best practices for establishing leadership or for leaders themselves for being effective leaders? I know that’s such a huge question! But yeah, Leadership 101 here.

E: Well, I think as a starting point, it’s useful to recognize that all of us, even if we’ve never studied leadership, even if we’ve never read a leadership book, we have what is sort of an implicit theory of leadership and followership, the way that we think that it should work. So sometimes that causes people to think, okay, well, the study of leadership is just common sense sort of stuff. And it depends. I mean, it is true that everyone has something as a starting point to like contribute to the conversation. But there’s also better and worse ways that we can approach this. And it’s not that, oh, we have good leadership here and we don’t over there, and so we just sort of ignore that space and go over here where we feel like the leadership is good. I think it’s important to recognize that all of us have the potential for a role in leadership.

So often, there are lots of scenarios where people are frustrated by leadership. There’s lots of research that suggests we have a leadership crisis in the United States and around the world. And I think that’s generally because people are looking at it, waiting for someone else to provide the leadership as opposed to them engaging in leadership for the issues. So really looking at opportunities to engage in that work: it starts with being curious about what could be, taking a humble approach and recognizing that any one of us has just a perspective, and it’s not that we’re just looking to find the right leader, but instead we’re trying to grow leadership, which may have a broad engagement.

That looks a lot of different ways. I think some of our implicit theories of leadership and followership we might need to abandon in order to go to whatever the next step is. There’s different frameworks, there’s lots of books, literature; some are grounded in research, some are not. But to the degree that they help us shift our perspective, I think there can be a lot of value.

I don’t have the book in front of me, but there’s a small book about the starfish and the spider and thinking differently about leadership in the sense of, from a spider standpoint, you have sort of a centralized, sort of component. And if you squash the spider in the middle, the spider dies. But if you cut a starfish in the middle, that may not be a good thing to do, but you haven’t actually killed the starfish, because there are parts that can continue to function. So some people use analogies like that to help us to think about what might be effective leadership as opposed to having sort of a centralized node and like all of the leadership comes from this source, but instead something that’s more interconnected and broader.

T: That’s really interesting. And it touches on a common issue in projects that I’ve been involved with, which is: you can invest a lot in building capacity more generally, but that includes skills that are relevant toward leadership - tools and structures even, so like village committees - and the big problem is turnover within those committees, or turnover within those people who have been exposed to the opportunity for that training. For example, in the case of Myanmar with the political situation there right now, but even before that, a lot of out-migration from communities searching for livelihood opportunities: there’s this, I guess you could say, brain drain. So that starfish model is appealing, because even if you have a key person or a handful of key people leave the community, you still have that kind of… remnant starfish parts, I guess… emerge and kind of reestablish leadership in that community.

But then how, on a practical level, how can, let’s say, a project that’s trying to engage with the community and it’s like, “we don’t really see particularly effective leadership structures at play”: f you were like a consultant, what would your advice be on how do you start cultivating leadership? I’ll just let you jump in there.

E: Well, it is true that it can be a real challenge to figure out where to start. And I think in many cases, starting point is figuring out where there’s an interest and where some people can get started on what they can do. And it can be small. I think if we look and we say, okay, well, what’s the small thing that any one of us or a small group of us can do and then sort of build some momentum from that, thinking from sort of a snowball scenario, you start with a small core and then figure out how to go from there and making some of that success visible.

There’s different ways if you’re trying to figure out, okay, but I still don’t know how to like rally people around like an idea or a vision. Storytelling is particularly powerful. There’s a book, the framing of which I really appreciate: Steve Denning has a book on the secret language of leadership, which is focused on storytelling. And he shares from his own experience of the value of a springboard story and his work at the World Bank. He really tried to convey some things with a lot of facts and details, and that wasn’t motivating any action until he had a single example of a successful story that helped people to imagine what could be. If this one story wasn’t just a one-off example, but if this was an everyday sort of occurrence, what would that look like? And as people get that vision, that helps develop some hope that there is a better way.

Because you may find people that agree that where we are is not where we want to be, but they just don’t have any sense of their own self-agency that they can do something or that there’s hope for something different. But if you come up with a single positive story that can give people some hope about what’s possible, and then they start crafting, together you can sort of form this vision about what we might like to be, what’s possible. And that can really grow and can take off like a fire does and really sort of going in a direction. But it has to start with getting some people together around some common ideas.

The Center for Creative Leadership talks about leadership in terms of direction, alignment, and commitment. If you’ve got some of those pieces where you’ve got a direction, an individual, you might be able to surface, like “this is what I think we ought to be moving for,” but you’ve got to align some other resources, other people in that, and then have some commitment sustained over time. Because if we don’t have some commitment over time, things will fizzle out. But that’s also where some of that distributed approach to leadership can be really useful because people are reluctant to take on a role that they feel like, “but I can’t stick with that forever.” But if we realize, okay, “but you don’t have to, like we’re just trying to get to the next step and there’s opportunities for other people to step into various roles,” it’s not that we’re relying on a single leader to carry the group, but instead each of us has something that we can do, something that we can contribute to move in the right direction.

T: I have some follow-up questions on that, but I also want to ask, kind of on the opposite side, and this can be specific to conservation or not, but what are some common missteps that you’ve observed in leadership? And that can be both, if we’re talking about conservation, from, let’s say, the professional conservationists within their organization or in how their organization engages with stakeholders or among the stakeholders?

E: I think a key part is not honoring different perspectives that people bring. And I think we can get caught up in our own perspective and what we see, and our push is to try to convince other people to see it from the way that we see it. But I think a key part starting point is to honor, to listen and respect what perspective someone else brings.

I’d mentioned the Center for Creative Leadership before, which does some really good work. A lot of that is in the business context, but they do some community leadership and nonprofit work as well. They have a framework where they talk about boundary spanning leadership. And what surprised me to begin with was, in order to span boundaries between groups and individuals, sort of these different perspectives, a key starting point is buffering, where you clarify what the boundaries are. And I thought, “gee, how does that work like that you focus on where these differences are in order to bridge them?” Because a lot of times the starting point would be, “oh no, let’s not talk about where we’re different.”

But I think starting with that of recognizing and trying to understand how are we different, honor what those different perspectives are, and then say, okay, in light of that, we can still find some common ground and we can appreciate where we can come together. I think that can be really useful. It starts with asking questions and inviting others for their input. There’s some good literature on leading with questions, which I really appreciate. And so as we think about leadership, our implicit models of leadership often cause us to believe that we have to be this great orator, speaker, you know, sort of telling people this grand vision. And that might be part of it, but you can accomplish quite a bit just by asking the right question that helps people to uncover what the possibilities are, as opposed to feeling like you need to direct them to some particular vision.

T: I love that. I mean, I’ve always been vaguely uncomfortable with how a lot of the conservation sector approaches conservation issues as primarily an issue of “we have to change behavior.” I understand on a practical level what they’re talking about, but there’s something about that approach where you’re immediately thinking of something as a deficit, like something is not as it should be and we have to change that. That feels icky to me.

E: Yeah.

T: And that kind of resonates with what you were just saying: these are not problems or behaviors that occur outside of a context and the solutions are not going occur in a vacuum, and understanding the sharing perspectives first to establish not only, like you said, honoring the differences (which I think is such an interesting point), but also I think it’s an important part of the process to establish like trust and communication. I really want to think about this more because it makes me feel more hopeful about establishing or promoting leadership in community settings.

One of my dissertation field sites, for example, had like nothing going on in terms of community organizations related to fisheries management or the marine environment. It was kind of like the Wild West. And some of my other sites had really well-organized fisher associations that had actively implemented some very effective management projects, like crab banks to improve their crab stocks. And I remember being like, well, if I had limited money, I would probably maybe focus on the more organized site just because I feel like there’s better chance for outcome. But on the converse, like, as you said earlier, you don’t have to give up on the places that don’t have amazing leadership out of the gates.

Those sites that don’t have those leadership structures feel like they might more urgently need that kind of support to create those conditions, to create the relationships where leadership can emerge.

Sorry, I’m rambling a little bit, but I’m just like, oh, this is so cool. I haven’t really thought of leadership as this collective phenomenon until I read that paper that you sent on eco-leadership. And that leads me to my next question. I’m definitely going to share a link to it in the notes and the transcript to this episode, but for people who just want to listen to a brief overview, could you provide that?

E: Yeah! So I had, for a long time, really felt like we needed to consider leadership that was more shared, sort of distributed, and really appreciated a lot of that. I’ve had some leadership roles growing up, and I was cautious about something that sort of seemed too domineering, you know, that people were sort of following my vision, but I wanted to figure out, “okay, what we could do together?”

Then when I went to graduate school, studied some more leadership and got into literature, I was really pleased to find some work that Simon Western had done, I believe it was actually for his dissertation, where he was studying these discourses of leadership over time and the way that people think and talk about leadership. And he identified this emerging eco-leader discourse. Each of these discourses emerges in response to essentially some concern or failure of leadership. And so it really helped me to sort of see that he was identifying this emergence of this ecosystems-based approach.

So it’s not necessarily just like sort of the natural environment, but thinking about sort of a systems approach to leadership and how that counters what has been a lot of the issues of a more hero-focused, sort of Messiah-focused discourse of leadership with, “oh, we just need to find the right person and they’re going to save the day.” And people have realized that doesn’t really work well. So it’s been great to sort of recognize that each of us has some of these perspectives that we’re bringing in. It’s not just all one or the other, but we can start to shift in this more shared approach to leadership.

I really appreciate some of the framing that Simon Wesson offered. There’s maybe two quotes out of one of his early books that I think are useful. He says, “Eco-leadership shifts power from individual leaders to leadership, in an attempt to harness the energy and creativity of the whole system.” Boy, there is energy here that we can put towards something! But if we just think it’s about individual leaders, we’re gonna miss that opportunity. This idea of leadership as opposed to focusing on leaders gets us with a frame where we can start thinking about possibilities differently.

And he also talks about, or describes, eco-leadership as a reciprocal process or a reciprocal relationship between leadership and its environment. It decenters individuals claiming that by creating the right culture and conditions, leadership will emerge. And so I think we can also look at different scenarios and say, okay, even if I’m not going to be identified as the leader, what can I do to create the culture and the environment where leadership can emerge in this space?

There’s other models that have leaned into that too. There’s a book on invisible leadership, and it talks about where the purpose ends up being the leader. So there’s different movements that people have described as “leaderless” because it’s hard to identify like, “Well, who is the leader of this movement?” But others have said, “Actually, that’s a leaderful movement, because it’s full of leadership. The fact that you can’t identify an individual leader isn’t a problem – that could be really successful.”

Now, those don’t always yield whatever the benefits are. So it’s things we’ve got to keep working on, it’s continuing to work on the environment and the culture that can allow this eco-leadership to flourish. But I think that’s really useful to start looking at that and to recognize that this systems-based approach is not about sort of the heroes. There are individual roles, but those roles are things that all of us can play a role in leadership, and it may be passing it off to other people too, and having a clean handoff of some of these roles can also be useful. So if I’ve created the right environment and I’ve handed off whatever my role is, I might be able to, you know, move on to another project or another area and that can be successful.

So the, the sort of older “messiah” discourse would say, oh, “if a leader leaves an organization or a project and things fall apart, that’s an indication that that was a really highly effective leader because when they left, things got bad.” But an eco-leader approach would say, “no, if this leader leaves and things fall apart, that may be a problem with the way that they were leading.” And somehow we need to figure out how it’s not so dependent on an individual, but it’s more of a collective approach to leadership.

T: Yeah, that’s so cool! I mean, this is such a paradigm shift for me. Again, I’m just in a very different field for which leadership is important. So my understanding of the concept of leadership is fairly, I guess, rudimentary. It is based on that kind of hero narrative, recognizing that having some kind of group cohesion is so important for implementing whatever it is that the leader decides. But this is so exciting to think of this as a more kind of distributed, like you said, harnessing of that energy.

It really reminds me of outcomes that I observed when I was working with this large multi-sector project in Myanmar, which had livelihood experts helping on livelihoods, governance experts helping with governance in a context of decentralization of resource management (which was happening during the 2010s in Myanmar), and then more specific fisheries management and biodiversity conservation. So there were a lot of great initiatives at building the capacity of village committees and of community members for different livelihoods, for example.

And I helped establish and pilot the participatory, qualitative evaluation of those efforts (we already had a pretty rigorous quantitative evaluation program). And one thing that kept popping up, which we hadn’t sought to measure was (and I promise this is relevant): confidence. Confidence in general, which also correlated with improved well-being, and also confidence in their abilities to collaborate and to communicate and to play a role in their community, especially for women, but also for men and youths. We were seeing this pop up again and again, no matter what domain we were evaluating.

For me, that really resonates with what you’re talking about: the projects we were doing, the activities that our project was leading, was creating, helping create a culture and environment where leadership can emerge by, I think confidence probably is, and as you said, the sense of self-agency, it’s so important.

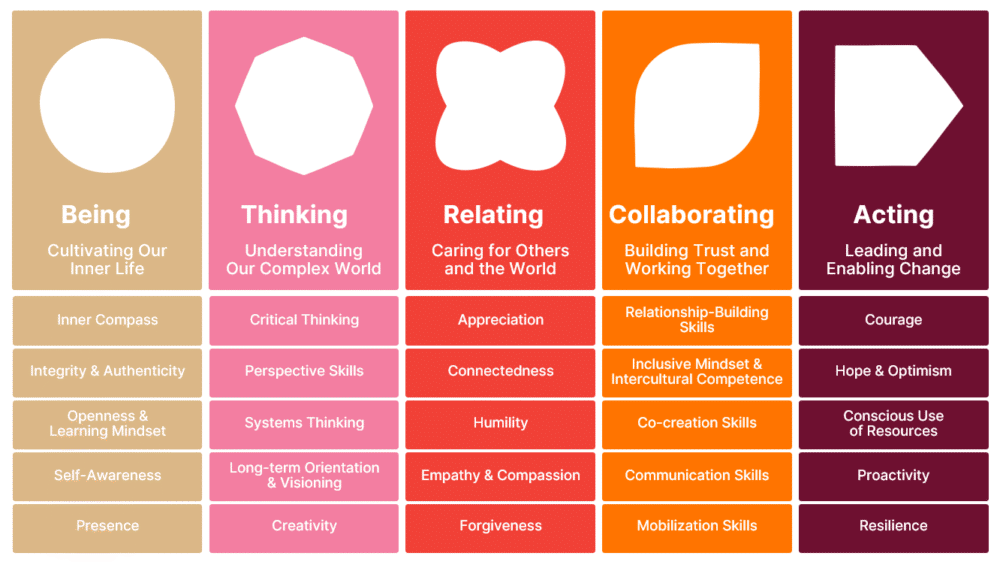

E: Yeah, I’ll just throw in another reference that may be useful. Probably listeners of the podcast are familiar with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and effort to make progress there. There’s a group that, after several years of looking at that and not seeing the progress that they were hoping for, highlighted the importance of Inner Development Goals. So there’s an Inner Development Goals framework, and it focus on five dimensions and skills associated with those. And it starts with being and this relationship to self.

And these aspects of confidence are a key part of that. Then it has a dimension of thinking, relating, collaborating, and acting. One of the things I like about that and the way that it connects with this eco-leader and eco-leadership paradigm is, for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, we have lots of people who say, “Yeah, that’s a good thing! We ought to have people that are working on that. I hope my government invests in that area!” But they don’t really see how they fit into that work.

The Inner Development Goals framework really helps position some of this and say, “look, if each of us work on these things and we start seeing about how we’re connected with these broader priorities, and then we’re prepared to engage where we can,” as opposed to, again, waiting for some leader to save the day and just move whatever resources. There’s a recognition that, “oh, there are things that each of us can do.”

And so the Inner Development Goals framework, I think, is really useful to help personalize some of these broader goals and visions, take it to a level and say, “okay, well, each of us can do something and we can help others with these Inner Development Goals and skills. And that’s a way that we might be able to make progress on these global priorities.”

T: Okay, I’m going to have to check those out! That sounds so, so interesting. And what you were saying about the hero leader resonates with how I’ve been doing a lot of thinking around the kind of work or efforts that receive, let’s say, prestige or recognition. And I’ve long been wary of a kind of celebrity culture that happens in, I think probably any human field, but definitely in conservation, you have some, well known that like the big international NGOs (BINGOs), but you also have some high profile individuals who get a lot of resources, a lot of recognition, more than a few of whom are known to not actually be that effective behind the scenes.

But along those lines, I recently read the book, The Good Enough Life. Let me quickly look. I am so, I’m totally blanking on the author’s name, but he tackles what he calls greatness culture. So it’s by Abram Alpert, The Good Enough Life. And he posits that this, you know, our kind of meritocracy, our focus on earning accolades through achievement actually misses out on a lot of potential good and humanity, by kind of minimizing the importance of the people who aren’t at the top. What is everyone else doing? What is everyone else expected to do? What does everyone else feel that they are capable of doing in terms of contributing something of meaning? And then how do we measure the worth of people’s efforts and contributions?

What you’re saying about this more decentralized eco-leadership aligns exactly with what that book was covering. And I can imagine that even within your field, there might be some resistance to this paradigm shift. Or is it just something that everyone’s excited about?

E: [laughs] Well, certainly there’s some resistance. There’s some heavy skepticism. Barbara Kellerman at Harvard University, in particular, has talked about the “leadership industry.” And the leadership industry, it’s a lot of money to be made in the leadership industry and developing leaders, and what people are willing to pay for is: developing themselves as an individual, or developing someone else as an individual. There’s not as much interest in this collective shared approach.

There are some groups that are doing it. Kansas Leadership Center really does a good job of taking a collective approach where they’ve done some work and tried to do some research to investigate this notion of “leadership development saturation.” If we’re trying to develop leadership among everybody within an organization, how do we get enough saturation that we really see the benefits that are there? So there’s some work on that, but I think even students that take a leadership class, they’re often coming in saying, “how do I become a better leader?” And they’re expecting some recognition for that leadership role. They aren’t necessarily coming into the class saying, “for this priority, this issue, I would like us collectively to figure out how to engage in better leadership.”

Now, sometimes we can help them with that shift in that frame and thinking, because there are things they really want to do and we can uncover, okay, what’s the process, what does that look like? I also think culturally, particularly in sort of our United States, Western culture that’s more individualistic and prioritizing individual people, we have a tendency to want to identify an individual to praise. And I think there’s some Eastern cultures that don’t have that same priority. That’s not where a lot of the leadership literature is, but there’s people that are looking into that and saying, okay, what can we learn from that environment?

There’s also a recognition that we might be able to harness more energy if we bring in folks who maybe don’t want to be in the spotlight. I’ve got a PhD student right now who is looking at some differences in perspectives between introverts and extroverts and how we might lose some more introverted people from leadership development programming. because they’re really not interested in some of the spotlight and some of the attention – the way that we approach our leadership development is not really appealing to them. So we’re not developing everyone in a way that we could get the best leadership out of it. There are some people that are really pleased to be seen as the leader, but that’s probably not where we’re going to get the best leadership from.

T: Yeah, that’s really interesting. Going back to the eco-leadership paper: one thing that was mentioned is, your team applied a mixed methods approach to studying eco-leadership, but also mentioned that this has been fairly rare and that studying this phenomenon is fairly challenging in terms of empirical examples from the real world instead of just as a concept. Can you share a little bit about why it’s challenging and how (I’ll have some questions about the specific methods later), but how you came to develop these methods or apply these methods to the challenge of studying this?

E: So one, the focus of that particular study, we were really interested in sort of more community organizations, sort of civic engagement. I actually started with the intent of being able to study some progress on restoration of Stroubles Creek, which goes through Virginia Tech and Blacksburg, Virginia, and there’d been a lot of progress there. When I looked into it, I realized that it was a lot more fragmented than I had anticipated. They had different people working on it, but it wasn’t in a situation where I could sort of study that as an intact sort of restoration effort.

But we looked broadly and said, okay, across the New River Valley, we have lots of different community groups that are engaging in projects. What can we know about the way that they approach that? What’s successful, what’s not? Can we study a variety of these groups and consider which ones are more or less successful and why?

We used a variety of different instruments to try to help get at that, but it’s a messy process. So a lot of research, when you can control all the variables, you know, even in psychology, they will sort of bring students in to study and control a lot of variables and try to just adapt one thing. In the real world, we don’t get the opportunity to sort of control all the variables. We have to deal with the messiness. And so trying to uncover that, we used some existing instruments that are useful, and I can talk about those, and what some of those looked like, but we also then wanted to follow up and say, okay, just beyond the numbers, we had people do some surveys and answer some questions, but can people explain why we’re seeing some of what we’re seeing?

So one thing that was really surprising from that study: the literature told us that group cohesion should be a key factor in success. And we had a measure of group cohesion, and it didn’t really indicate that group cohesion was a key factor in the success. And I tried to figure, okay, well, why is that? Like what’s going on? We ought to be able to see some benefit there.

But in conversations as we followed up and did some focus group interviews with the participants, they were able to articulate, well, what type of cohesion was really helpful? And people said, “look, the people we’re coming together with, we’re really glad to come together and work on these projects and what we’re doing. But these aren’t the same people that I hang out with, you know, just for fun.” That helped us to realize there was some task cohesion, like people coming together that “we have a common focus on what we’re trying to get done, and it’s okay if we have different social interests and, you know, we don’t have to be engaged in a lot of social things in order to be productive.”

For me in particular, one of the things that was exciting about that is I’ve been told, “oh, the way you make some of these good connections is, you hang out at the bar and you’ve got to have like all of these social connections.” And I’m on the more introverted side and I can do some of that, but I think, “gee, that’s, it takes a lot of energy for me to engage in some of those environments.” This idea that the task cohesion might be more important than the social cohesion of the group helped me to realize: okay, we can talk through specifics in terms of what we’re trying to do and get people excited about that, and that in itself may be what allows us to be successful or more successful than another group.

T: I love that! As a fellow introvert and someone who’s worked in fishing villages and I’m a vegetarian and I don’t drink alcohol. And that’s like with people who don’t kind of think about it too much, like “you have to eat seafood, you have to drink with the fishermen,” and especially as a woman in some of these rural communities, where culturally it’s not that seemly for a woman to be drinking with a group of men alone, you know, it’s just like all these barriers… and yet I’m like, I don’t feel like I need to do all that, I feel like I’ve done okay without doing that. So it’s great to hear that this notion of task cohesion in that.

And I’ve always felt that stakeholders, be it fishermen or fishing families in coastal communities or the folks working on this, was it this creek restoration? They’re very capable of engaging with other humans, like you said, on this task; you don’t have to entirely mesh on the social level in order to be able to work together, so I’m glad to hear that, personally.

E: Well, and that helps people to work together. They may disagree on a variety of other things, but they can say, look, “we’re still gonna work together because this thing is important, and so we’re gonna invest in that.”

T: Okay, that’s really helpful to know. And I’m not gonna ask specific questions about the methods used. It’s just, you know, there are some tools that were referenced like the group cohesion scale and the team multi-factor leadership questionnaire. As someone who’s just interested in learning more about how one tries to get a grasp of what this thing called leadership is, are these commonly used tools in your field? Where are they rooted?

E: So they are related to leadership literature, small group communication, some of those pieces that I think are really relevant. The group cohesion scale was one that I picked up on that others had used and then I realized, okay, there would still needed to be an adjustment in the way that things to think about it for the context that we had, because we needed to distinguish more between the social and the task cohesion.

The team multifactor leadership questionnaire really looks at transformational leadership, but it includes aspects of transactional leadership where people can assess that. And it’s asked them to assess it for the group. I’m sad that it hasn’t gotten more use, but it gets back to your earlier question about, are those in leadership studies in that realm, are they really bought into this eco-leader approach? And I think the reality is a lot of it is still very individualistic, where the team multifactor leadership questionnaire decentralizes that notion of leadership away from an individual, but instead looks at a group level. And it does ask people to reflect on what they’re seeing in the group, and I think there’s a lot of value in that.

Much of the way that we approach this research is self-assessments. We can do sort of 360 assessments, where you ask someone to identify other people that they know to rate them, so that can be useful. But when we’re trying to look at how leadership might work in a group setting, asking people to sort of share what they see in that group can be really useful. And then that gave us some specific quantitative measures to look at correlations and see where are some of these connections that might be really helpful to dig into. And then I was really glad to be able to engage several of these groups in some focus group follow-up discussions afterward, to get their take on it. Because we can look at the numbers and say, “oh, these are the connections that I’m seeing,” but having their words to be able to explain how they perceive it really works in those settings makes a big difference for us understanding what’s going on.

E: Obviously, there’s a literature and kind of a bank of tools, but I will say that natural scientists moving toward more social sciences do tend to underestimate the existing body of work in those other fields. But also, when I have in my spare time kind of a moment of “oh, I’m interested to learn more about leadership, let me look up how it’s studied,” the finding that the results online are just flooded with, you know, business-centered contexts or even the more kind of fluffy “develop leadership skills!” but it’s not rooted in anything beyond that.

E: Yeah, there’s some books on environmental leadership that people can pull up, and I think those are useful. I’ve contributed some chapters to some edited books there. But it does take some searching. It’s not typically the book that you’re going to see in the airport that you can pick up. There’s not a lot there. Some of the environmental leadership books might be a little bit academic, you know, in terms of their focus, but others can be very practical. And so, I don’t have a single source to direct people to, but just encouragement to keep looking. So if, you know, someone finds a book and they’re like, “oh, I don’t know that that really helps”: keep looking, because there is some good leadership literature out there, it’s growing, and I think the relevance for the environmental sector is really important.

There’s a lot of value in doing some self-reflection. I think that’s important. I also think it’s really useful to read and learn about what other people are seeing and to realize, okay, there’s some other frameworks that I can latch onto. Sometimes It’s a matter of giving words to something that you felt, but you didn’t know how to talk about it. And so that’s where the leadership literature sometimes could be really useful, where someone says, “yeah, I’ve sort of known that, I just didn’t know how to explain it, and so I’m glad to have this model, this framework that helps me to talk about it with others.”

T: Absolutely. And it’s just great to know, to have your reassurance that those resources are indeed out there. I definitely hope to find the time to actually dig in and get to some of those. And speaking of resources, could you share a little bit about the Collaborative Community Leadership Program?

E: Yes. So when I started here at Virginia Tech, there was already some leadership coursework and programs, primarily at the undergraduate level. And I was looking to sort of see where we could grow some of our programming. And I’m in a College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, not in a College of Business and trying to look and see what makes sense. I did find there were some graduate coursework at different places around the university. They didn’t always know what each other was doing. And so part of it was saying, okay, how do we elevate some of this and help students find where some of these courses are? Then also combining some of these pieces where we have a foundational component.

So this graduate certificate can be completed standalone. It doesn’t have to be as a degree program, but it is credit bearing. So students are enrolled in in formal classes, and we have 2 foundational classes that really get at leadership theory and practice that help ground people in the literature. And then students are able to build a program with a couple other electives that align with where they want to apply leadership. And so on the website, we have some suggested courses, but students can propose how this fits in. So we’ve got students in public health and communications that are bringing in some of those contexts and tying it in with the leadership. And then the culminating piece is whoever’s pursuing the certificate puts together some project in terms that reflects their application of their insights gained. And that can look a lot of different ways.

But when I was putting together the graduate certificate, I didn’t want it to be, oh, as long as somebody passes these classes with like a C or better, they get the certificate. I thought, no, I want people to be able to somehow pull this all together and convey what are they doing with it. So that’s what the project requirement is. It allows people to take an idea that they have, apply these leadership concepts to it, and just share some of those insights.

It’s something that people can complete totally remotely virtually. We have on campus classes as well. But if somebody is interested in pursuing that, they could contact me and I’d be glad to have conversations about it.

T: Oh, that’s so cool. I know a number of people who would be interested in that. And that’s such a great model as well. Just as a lot of my work interests and background is transdisciplinary processes, a challenge with teaching that in a university setting is maybe, as you know, kind of establishing a cross-cutting entity across different

departments and programs. So that’s a really cool example.

I have two more questions, trying to squeeze that into our final minutes. The first one I hopefully is quite brief, or you can answer it fairly briefly: in your field, kind of as an academic field, what is the pipeline from research to application?

E: It can look a lot of different ways. Part of the reason why I’m hesitant to sort of lay it out with a pipeline is there are people that are successful, but there’s not a lot of recognition of that success that allows us to replicate it. So partly what I try to look for is: where are some good examples? Where are some people having success and how do we elevate those examples and share that with others?

There is some basic research that we can uncover. I try to draw upon both psychology and sociology and what are we learning about those models and frameworks. How do we elevate that in a way that we might be able to test something out in maybe an educational program? Sometimes that’s formal, but sometimes we look for non-formal education. I have an extension appointment, and so we do community education, and we can test out some of these models, sort of see what works well for people, do some follow-up interviews, surveys, things like that, and then try to elevate these examples.

It’s, in many cases, combining a variety of case studies to fill out a larger picture of what’s possible. So in that space, people can choose small tweaks and adjustments. “Oh, what if we change this? What if we consider this approach?” Whether it’s intact programs that makes an adjustment to their curriculum, or maybe there’s a way to change some of the framing of what we’ve outlined. Change can be challenging, but if we can figure out, okay, what’s the small step that somebody might be able to test out and, you know, really approach this a little bit like from a scientific mind and say, how do I test out this change and apply that to leadership? And I think some people just hadn’t really considered that possibility. But if you take this sort of scientist approach to the work and say, Okay, I’m gonna try this small adjustment, monitor it, see if it works.

Then the thing that is often missing is: we need to figure out how do we share that more broadly so that that little experiment doesn’t benefit just an individual or a group, but how do we share that more broadly so that people could be more successful?

T: Okay, thank you. I’m just always curious about, that connection there. And I’d like to finish off with a fairly open question, but: do you have any advice for people working in conservation – so, people similar to me, let’s say with a similar background of knowledge - who want to either do a better job supporting and amplifying leadership in the places where they work, in the communities where they’re engaging, and/or want to grow as leaders themselves for their own role in the conservation sector?

E: Yeah, I think a key part is having that grounding in humility and curiosity. I think if you start there, you’re creating the environment where this more collective approach to leadership can flourish. I think, you know, individually being able to focus on those Inner Development Goals and say, how do I improve myself in some of these areas, and then being able to expand that in my interactions with others and action.

I think storytelling can be particularly useful. There’s some good literature about storytelling, but being able to think in terms of stories: sometimes it can get so focused on the facts and the details, and I feel like you need to be able to know this information, but sometimes just having the story helps to be able to expand the movement in a way that otherwise we would miss out on people’s engagement. And so I think that’s really important: how do we take the interest that we have and turn it more into a movement? How do we expand that in a way that we get lots of people working towards this effort?

And then from there, I would just say: keep learning. I think there are lots of ways to learn. My hope individually for myself is that I continue to learn and grow over time. And that’s what I try to convey to other people too, is to see themselves as a lifelong learner and say, okay, I’ve been successful here. What’s that next piece that I want to learn about to continue to grow and develop?

T: That’s fantastic advice - thank you! And thank you so much for this interview. If I could hog your time any more, I would have so many questions, but I appreciate the time you’ve already generously shared with me and so many resources for me and listeners to follow up on. So thank you so much. This was perfect. I really enjoyed it!

E: Great! I really enjoyed it too. Thanks for inviting me. Thank you.

T: All right, take care.

-

ABOUT DR. ERIC KAUFMAN

Dr. Eric Kaufman is a professor and Extension specialist at Virginia Tech, where he also serves as associate head of the Department of Agricultural, Leadership, and Community Education. His research and outreach focus on leadership-as-practice, with particular attention to collaborative problem solving, team development, and community engagement. Eric developed Virginia Tech’s graduate certificate in Collaborative Community Leadership and has worked with partners across agriculture, natural resources, and community organizations to strengthen shared leadership. He is a past president of the Association of Leadership Educators and the Virginia Tech Faculty Senate, and he has contributed to more than 40 funded projects supporting leadership and community development